It’s safe, effective, with no side effects or risks. Sounds too good to be true? it just might be…

Thermography is the topic of this weeks Dr Rachie reports.

I refer to it as “The Safe Breast Cancer Screening Test Your Doctor Isn’t Telling You About” because this was what popped up on Google when I searched for information.

Clued up sceptics would know this is one of the classic red flags to alert you to pseudoscience. In fact it has been used in the title of just about every book written by Kevin Trudeau, the infomerical billionaire from the US, who peddles all kinds of fantastical products and has been fined for doing so.

If you’re not familiar with the seven signs of pseudoscience, then it would be wise to become familiar with them to protect yourself from getting conned.

Dr Robert L Park published an article in the The Chronicle of Higher Education, Jan 31, 2003. in 2003, detailing the red flags to alert you to pseudoscience and the article has since been republished on Quackwatch.

1. The discoverer pitches the claim directly to the media.

2. The discoverer says that a powerful establishment is trying to suppress his or her work.

3. The scientific effect involved is always at the very limit of detection.

4. Evidence for a discovery is anecdotal.

5. The discoverer says a belief is credible because it has endured for centuries.

6. The discoverer has worked in isolation.

7. The discoverer must propose new laws of nature to explain an observation.

A little about breast cancer.

See Breast Cancer Australia for more information.

- 1 in 11 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer before the age of 75.

- Breast cancer is the most common cause of cancer related death in women in Australia.

- The incidence of breast cancer has risen over 18% from 1995 to 2005.

- In Australia in 2005, a total of 12,170 women and 95 men were diagnosed with breast cancer and there were 2,683 deaths.

So, what is thermography?

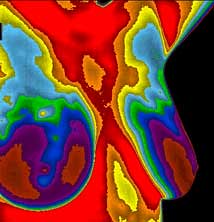

This technology was originally designed for US military use in night vision but also has many applications in medicine (Arora N. et al., 2008). The principle of medical thermography is the detection of small temperature differences in the body which are then transformed into thermal images that the practitioner interprets. The theory is that abnormalities such as malignancies, inflammation and infection emit increased heat that will appear as hot spots on images.

Breast thermography, also known as thermal breast imaging, is a technique that produces “heat pictures” of the breast, by measuring the temperature of the skin of the breast. The rationale for thermography in breast imaging is that the skin overlying a breast cancer can be warmer than that of surrounding areas.

Limits of thermography

Thermography was approved by the FDA in 1982 as an adjuct tool for breast cancer detection. Its applicability, however, was limited by the temperature resolution capability of earlier imaging technology, the bulky equipment necessary to perform procedures, and the general lack of computer analytical tools (Arora N. et al., 2008). Thermography is also limited in that it only indicates if a difference in temperature exists. The diagnostic significance of this information remains unclear. It has not been proven that performing thermography eliminates the need for other diagnostic studies, nor has it been demonstrated that any additional diagnostic value is provided by thermography.

Although thermography is a noninvasive low-risk procedure (i.e., no harmful rays are emitted), several disadvantages have prevented its widespread use. It requires a tightly controlled environment free from draft, temperature fluctuation, and humidity. It also requires a 20-minute to two-hour acclimatization period.

Does thermography detect breast cancer?

In 2004, the New Zealand Health Technology Assessment conducted a review of the scientific literature to establish the efficacy of thermography as a screening tool and adjunctive diagnostic tool. They scoured Pub Med, turning up 1,154 abstracts which matched their search criteria, from which 85 were selected for full text and three were used in the review. They reported;

In 2004, the New Zealand Health Technology Assessment conducted a review of the scientific literature to establish the efficacy of thermography as a screening tool and adjunctive diagnostic tool. They scoured Pub Med, turning up 1,154 abstracts which matched their search criteria, from which 85 were selected for full text and three were used in the review. They reported;

“The evidence that is currently available does not provide enough support for the role of infrared thermography for either population screening or adjuvant diagnostic testing of breast cancer.”

Whilst there are studies demonstrating that thermography can be useful as an adjunct tool in breast screening (see Arora et al., 2008), this evidence is sparse and likely explains why cancer bodies and governments remains cautious about recommending the procedure.

BreastScreen SA has this information about thermography:

“According to several reviews there is no current scientific evidence to support the use of thermography in the early detection of breast cancer or in the reduction of mortality from breast cancer. The results of thermography in various studies are inconsistent, but overall, thermography produces an abnormal result in too many women who do not have cancer, and it misses cancers that are known to be present in other women.”

The scientific, peer-reviewed literature and professional societies do not support the use of thermography as a reliable indicator for the presence of breast cancer (Hayes, 2006).

And this also from the BreastScreen SA website; “There is a high level of consistency in the approach of numerous medical organizations from Australia and abroad in warning against the use of thermography for breast cancer detection. The following organisations support the use of mammography and do not support the use of thermography for breast cancer detection (valid as at May 2007):”

Not that this prevents the alt med guys from spruiking it anyway, never mind the pesky evidence. One such case occurred recently when Mike Adams from the website Natural News reported on new findings about the risks associated with mammograms. No medical intervention is without risk and mammograms are no exception since small doses of radiation are used to image the breast tissue.

Several recent studies have shown that for women at high risk for breast cancer, getting early scans, beginning before the age of thirty, can increase the risk of getting the disease between 1.5 and 2.5 times. For this reason The US Department of Health and Human Services changed the recommendations for mammograms on November 19th 2009, advising that they should now be started at age 50 and performed bi-annually, up from 40 years of age.

Among women who have BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations, the lifetime risk of breast cancer is 36% to 85%, and the lifetime risk of ovarian cancer is 16% to 60% (Jantoi et al., 2008) therefore, regular screening from a young age is important. The BRCA1/2 genes are known as “tumour suppression genes” and as such are responsible for correcting DNA mutations; mutations that may well result from radiation damage (Kennedy D.A., et al., 2009). As such, is it important for women with these mutations to discuss the risks of mammograms with their doctor and consider alternatives, such as MRI and ultrasound.

Mike Adams on Natural News reported findings from a recent study about the risks of mammography as “Study verifies mammography screenings cause cancer!” which is a completely misleading interpretation of the findings. To reiterate, they may increase the risk by a much as 2.5 fold, but they do not cause cancer. So if you are unlucky enough to have the double mutation and have a 60% chance of getting cancer, with the increased risk of 2.5 fold, you then you have a 120% chance. Not very good odds, which is why many such women who have this mutation get double mastectomies.

Mike then proposed that women get MRIs or thermography instead. Thanks for the medical advice Mike.

In line with the unreliability of thermography, BreastScreen Australia has published a position statement on their website stating; “ The National Advisory Committee to the BreastScreen Australia Program does not recommend the use of thermography for the early detection of breast cancer” for the following reasons;

Studies have shown that a tumour has to be large (several centimetres in diameter) before it can be detected by thermography (Homer 1985). Screening mammograms have the ability to detect breast cancer at a much smaller size, and therefore to reduce deaths from breast cancer. Less than 50% of breast cancers detected by mammography screening have an abnormal thermogram (Martin 1983).

Thermography was also cited in a recent parliamentary enquiry in South Australia into what the AMA called “bogus” therapies, along with colonic irrigation, claims made by some chiropractors about “subluxation”, cures for cancer, and some erectile dysfunction treatments. The AMA has concerns about “quackery”, telling the inquiry that unregulated practitioners are a “relative risk to patient health and have enjoyed immunity and lack of scrutiny from the legal and regulatory authorities which apply to the medical profession”.

Take home message

The take home message is that thermography is unreliable – missing known cancers and diagnosing non-existent cancers – and also expensive at around $200 US dollars. But don’t take my advice or that of Mike Adams from Natural News, talk to your doctor.

———

References

Arora N., et al. Effectiveness of noninvasive digital infrared thermal imaging system in the detection of breast cancer. The American Journal of Surgery. 2008; 196: 523-526.

Hayes Search and Summary™. Digital infrared imaging (thermography) for detection of breast cancer. Lansdale, PA: HAYES, Inc.; ©2006 Winifred S. Hayes, Inc. 2006 Apr 2.

Homer MJ. Breast Imaging: Pitfalls, controversies and some practical thoughts. Radiological Clinics of North America 1985; 23: 459-471

Jatoi I. and Anderson W.F., Management of women who have a genetic predisposition to breast cancer. Surgical Clinics of North America. 2008; 88: 845 – 861.

Kennedy DA, Lee T, Seely D. A comparative review of thermography as a breast cancer screening technique. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2009; 8: 9-16.

Martin JE. Breast imaging techniques, mammography, ultrasonography, computed tomography, thermography and transillumination. Radiological Clinics of North America 1983; 21: 149-153

Browse Timeline

- « No Natural News, mammograms do not cause cancer.

- » Paul Offit, Wired and Amy Wallace sued for defamation.