Many readers, especially Australians, would be familiar with “blue-green algae”. In particular, if you have spent any time in South Australia, you may recall periodic government alerts warning against drinking the water or using it for recreation during outbreaks or “blooms”.

The term algal ‘bloom’ describes an increase in the number of algal cells to a point where they can discolour the water, produce unpleasant tastes and odours, affect shellfish and fish populations and seriously reduce the water quality (1). Since many types of algae produce toxins, they can also make you very sick and have been responsible for the deaths of livestock and marine species.

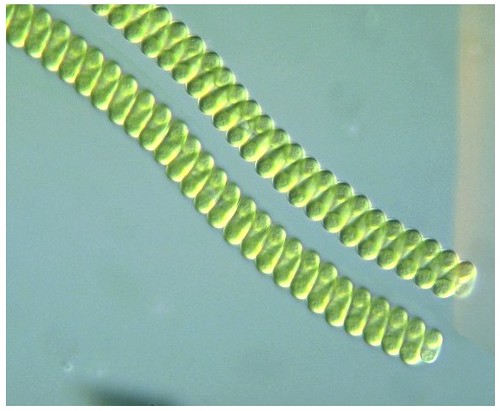

Blue green algae, also known as cyanobacteria, are in fact photosynthesizing bacteria, which are green when metabolising and turn bluish when the scums are dying. Cyanobacteria live in terrestrial, fresh, brackish, or marine water, but can also live as symbiots in the roots of plants.

Blue green algae, also known as cyanobacteria, are in fact photosynthesizing bacteria, which are green when metabolising and turn bluish when the scums are dying. Cyanobacteria live in terrestrial, fresh, brackish, or marine water, but can also live as symbiots in the roots of plants.

Algal blooms occur in all types of waterways and water storages, and bloom when nutrients and light are high. Whilst not all species which make up algal booms are toxic, there is no way to know, until you test them, so it is better to steer clear. Toxicity also varies with the seasons and environmental conditions.

The toxins, including domoic acid and BMAA (a neurotoxin) are released as the bloom dies and the cells become ‘leaky’. Domoic acid has been implicated in serious food poisonings, even deaths associated with shellfish and BMAA in neurodegeneration such as Alzheimer’s disease, ALS (Lou Gehrig’s disease) and an ALS/Pakinsonism-dementia complex of Guam (Guam’s disease).

Australia – a history of blue green scum

Toxicity associated with blue green algae has been documented as far back as the 1850s, where accounts by European explorers and settlers contain numerous references to scums or discoloured water (2). Some reports also suggest the Australian Aboriginals had been aware of the poisonous nature of blooms as far back as 1850 (3).

The earliest documented scientific evidence was published in Nature in 1878 in a paper called “Poisonous Australian Lake.” The report described “..a bloom of Nodularia spumigera floated to the lake surface and was wafted to the lee shores, forming a scum 2–6 inches thick” (4).

Large numbers of livestock ingested the scum via drinking including horses, sheep and cattle and later died and one woman became seriously ill. The deaths and publication of the Nature paper created a heightened awareness amongst the public, leading to warnings, and police troopers stationed at various points along recreational and drinking water bodies, to warn of approaching blooms.

In the Summer of 1991-1992 an enormous bloom occurred in the Barwon-Darling River System in NSW. This bloom spread over an area spanning 1000 km and remains today the world’s largest Algal Bloom (5).

When birds attack; the Hitchcock connection.

But it’s not only livestock and humans who are at risk of illness when exposed to algal blooms. A very famous case of sea life allegedly falling victim to algal blooms occurred in California, USA.

But it’s not only livestock and humans who are at risk of illness when exposed to algal blooms. A very famous case of sea life allegedly falling victim to algal blooms occurred in California, USA.

In the early morning hours of August 17, 1961, residents of Santa Cruz were invaded by a massive flight of sooty shearwaters slamming into their homes and littering the streets and town. The Santa Cruz Sentinel Sentinel reported the incident under the headline; ‘Seabird Invasion Hits Coastal Homes’

‘…When the light of day made the area visible, residents found the streets covered with birds. The birds disgorged bits of fish and fish skeletons over the streets and lawns and housetops, leaving an overpowering fishy stench.’

Several theories exist as to the cause of the mass destruction and death. The first explanation was offered at the time of the incident by museum zoologist at the University of California, Ward Russell, who proposed that the birds were disturbed whilst feeding, became disorientated in the heavy fog that layered the coast that morning and headed for the light of the town, including torches held by curious residents, thus appearing to “attack”.

But scientists now speculate that ingestion of anchovies contaminated with toxic algae may have played a role.

What is known is that the incident sparked the interest of an author across the globe in Cornwall, England whom several years earlier in 1952, had also been attacked by birds, but in a very different scenario. In an autobiography of author Daphne Du Maurier called “The Private World Of Daphne Du Maurier”, author Martyn Shallcross describes Du Maurier was walking her dog by a lake, when two hungry seagulls attacked her dog then her, forcing her to seek shelter under a nearby tree. The result was the 1952 novellete “The Birds”.

Four days after the 1961 sooty shearwaters incident in Santa Cruz, the Santa Cruz Sentinel had another story to report,

“Hollywood mystery producer Alfred Hitchcock phoned The Sentinel Saturday to let us know he is using last Friday’s edition as research material for his latest thriller.” (August 21, 1961; page 4).

Apparently, the movie version of Du Maurier’s book was already underway under the supervision of Hitchcock, but the Santa Cruz incident may have inspired him to change the location from the quaint hills of Cornwall, England to Bodega Bay California, where his 1963 “The Birds” thriller was eventually set.

Evidence for a role for algal bloom poisoning in a mass disorientation and death of sea birds was presented in 1991, when a similar incident of unusual bird behaviour was observed around Monterey Bay in California. Studies of the dead birds, including brown pelicans and Brandt’s cormorants showed they were poisoned by domoic acid, probably from the anchovies that the birds fed on. Domoic acid is excreted in large quantities during plankton blooms, thus posing a risk for sea creatures that feed on plankton, and larger creatures further up the food chain.

Human poisonings have also been documented, some fatal. In 1987 a hundred people on Prince Edward Island in Canada suffered from dizziness, nausea, and memory loss after consuming contaminated mussels. On this occasion, four people died from the effects of the toxin.

In Brazil in 1996, 101 of 124 dialysis patients who received dialysis with water contaminated with cyanobacteria suffered acute liver injury,and 50 died. An investigation revealed the water used in dialysis had not been sufficiently treated and contained toxins known as microcystins. These patients reported similar symptoms to the food poisoning cases, including visual disturbance (i.e., blurred vision, scotoma, or nightblindness), nausea and vomiting, headache, and muscle weakness.

In November 1979 an outbreak of hepatoenteritis at Palm Island, in northern Queensland, involved 148 people, mainly children, the majority of whom required hospitalization. The outbreak occurred a few days after the supply authority treated the dam with copper sulphate to kill the algae, which in turn burst the algae, releasing the toxins into the water. A week later people who had drunk the water became ill, with signs of gastrointestinal, liver and kidney damage. (Interestingly, the conclusion that microcystins were the culprit has since been challenged by an author who said this was a cover up for copper poisoning resulting from the supply company ‘over treating’ the water).

A more recent hypothesis regarding disorientation amongst sea creatures leading to death as a result of acute plankton or cyanobacteria poisoning, is the phenomenom of whales beaching. This does not seem so unreasonable when you consider that algal blooms, occur regularly in the oceans, all over the world some so large, they have been photographed from space.

But it’s natural so it must be good for me!

So we now know that blue green algae can be toxic to both humans and animals, in some cases fatally. Sure it’s natural but this doesn’t necessarily make it safe. Cyanide is derived from the kernels of apricots – it’s completely natural but it will kill you. The Ebola virus is natural, but you will suffer an excruitiating death as your organs slough out your orifices.

So we now know that blue green algae can be toxic to both humans and animals, in some cases fatally. Sure it’s natural but this doesn’t necessarily make it safe. Cyanide is derived from the kernels of apricots – it’s completely natural but it will kill you. The Ebola virus is natural, but you will suffer an excruitiating death as your organs slough out your orifices.

As such it puzzles me is that you can buy cyanobacteria from your local health food store in a powder or tablet form marketed as spirulina. Touted as “100% Pure and Natural”, “nature’s superfood” and “Totally natural product” spirulina is nevertheless blue green algae meaning contamination with BMAA and other toxins can not be completely discounted.

Following the publishing of a paper from Cox et al. in 2005 (6) which reported 30 types of cyanobacteria were contaminated with BMAA, the Spirulina industry went into overdrive to ensure their customers that their products were safe. Several issued press releases emphasising (correctly) that the Cox paper did not test spirulina. One company, Cyanotech Corporation apparently approached Cox to test their spirulina for BMAA to which they say “he did not respond”1.

“The Company then enlisted the services of Professor Wayne W. Carmichael, Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences at Wright State University and a leading expert in the field of cyanobacterial toxins. On June 3, 2005, Professor Carmichael reported his findings confirming the absence of detection levels of the suspected neurotoxin BMAA in Cyanotech’s Spirulina Pacifica.”

This is good news, for this batch of spirulina and for this company. But what about other producers of Spirulina? As discussed earlier, biological variability dictates that levels of toxins synthesized by cyanobacteria are different from season to season, time and lifecycle at harvest. For some of their lifetime blue-green algae may have no toxins, other times large quantities. If I was a consumer of spirulina (and why would I), I would want every batch tested before I take it.

In another press release from by Earthrise Nutritional they stated;

“It should also be pointed out that the connection between BMAA and Alzheimer’s disease is far from certain. Dr. Paul Alan Cox’s group has not made any definite connection in their report, and other experts in the field have expressed their reservations.”

This cyanobacteria/BMAA hypothesis was first proposed by Cox and colleagues including Dr Oliver Sacks when they found BMAA in the brains of Canadian and Guam Alzheimer’s patients but not in control patients (7) and further evidence has followed (8-9). This hypothesis has been further strengthened with recent findings from scientists at the University of Miami, where BMAA was detected in brain and spinal cords of ALS patients (10).

Similarly, veterans of the Gulf War have increased incidences of ALS at a younger age than the rest of the population. Studies into the cause included analyses of the deserts of Qatar and showed that 56% of the area consists of cyanobacterial crusts and mats which contained BMAA (10).

Similarly, veterans of the Gulf War have increased incidences of ALS at a younger age than the rest of the population. Studies into the cause included analyses of the deserts of Qatar and showed that 56% of the area consists of cyanobacterial crusts and mats which contained BMAA (10).

Further, an elegant “Google Maps” epidemiological study of a cluster of ALS patients in New Hampshire, USA revealed that many had resided by water bodies which had been subject to frequent algal blooms (11).

Although the cyanobacteria/BMAA hypothesis is not yet proven, the evidence is compelling enough for me to think twice before I consume spirulina. Especially when one grower has the following listed as “slight side effects”;

- Slight fever due to the body’s need to burn the extra protein from Spirulina

- Slight dizziness. If this occurs, take less of the product. If the symptom does not improve please stop taking Spirulina

- Thirst and constipation. After taking a high volume of Spirulina we recommend at least an extra 1/2 litre of water per day to help our body absorb the Spirulina

- Stomach ache

- Skin itch or slight body rash

(my emphasis)

Remember the 100 people from Prince Edward Island who were poisoned by shellfish? They;

“…suffered from dizziness, nausea, and memory loss after consuming contaminated mussels.”

Correlation does not equal causation but the similarities are interesting nonetheless.

——

Footnotes

1. Strangely I can find no trace of the original Cyanotech press release associated with them, only reports on other websites.

References

(1) http://www.derm.qld.gov.au/water/blue_green/blue_green.html last accessed January 5th

(2) http://www.publish.csiro.au/paper/MF9940731.htm last accessed January 5th 2010.

(3) Francis G. 1878. Poisonous Australian Lake. Nature (London) 18, 11-12.

(4) http://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/720907

(5) Cox et al. 2003. PNAS 100:13380-3.

(6) Cox et al. 2005. PNAS 102:5074-8.

(7) Murch et al. 2004. PNAS 101:12228-31.

(8) Murch et al. 2009. Acta Neurol Scand 120:216-225.

(9) Bradley and Nash. 2009. ALS S2:7-20.

(10) Cox et al. 2009 ALS S2:109-117.

(11) Caller et al. 2009 ALS S2:101-108.